Ethics Study: Subsistence Living vs. The Western Lifestyle

- Gaby Tiu

- Nov 24, 2020

- 8 min read

This ethics study offers an exploration of the environmental approach to subsistence living and how Western living standards undermine its efficiency. (June 5, 2020)

Re-Defining Poverty: The Dangers of Trying to Fix Subsistence Living

Introduction

What do we think of when we imagine poverty? Maybe we picture what extreme poverty often looks like in our own country, the United States, with homeless people lining city streets, tent cities under highway bridges. In our immediate communities, many of us Americans have seen people on sidewalks with cardboard signs seeking money or food. Perhaps we picture poverty outside of Western culture, with a depiction of other societies’ members living a seemingly low-quality life, at least by our own standards of what it means to live comfortably. However, what if our conception of poverty is not universal, but specific to the Western and colonial perspective?

In several ways, this applies to many common Western conceptions of poverty, conceptions which subsequently threaten the lives of indigenous groups as well as the environment. Western beliefs around poverty and what it means to have a high-quality life can be dangerous perpetuations of colonialism, which not only feed into the spread of industrialization and capitalism, but also potentially ignore real poverty-related problems in favor of disrupting indigenous lifestyles. In particular, such a lifestyle is subsistence living. Western views around subsistence living ought to be changed otherwise they risk resulting in infringements on indigenous lifestyles and contributing to the dangerous industrial-centric views present in Western society, as is described in Vandana Shiva’s Staying Alive. The benefits of subsistence living are also described in “Living off the Land”: How Subsistence Promotes Well-Being and Resilience among Indigenous Peoples of the Southeastern United States, and the consequences of disrupting that are discussed in "We Can Not Get a Living as We Used To": Dispossession and the White Earth Anishinaabeg, 1889-1920.

Defining Poverty

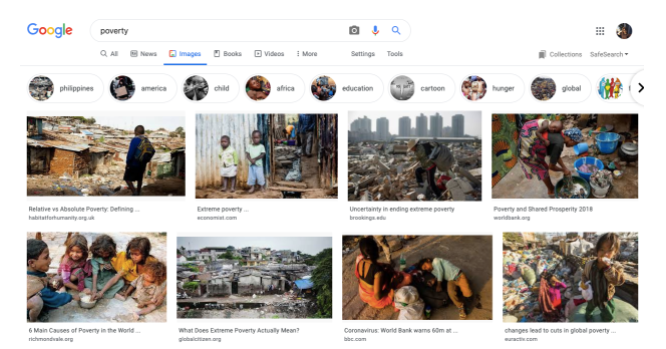

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines poverty as “the state of one who lacks a usual or socially acceptable amount of money or material possessions” as well as “debility due to malnutrition” (“Poverty”). In our immediate industrialized setting in the US, many of us have seen a range of poverty close-up. Poverty in urban or suburban settings can look like a large family crammed into an apartment, all struggling to make money with minimum-wage jobs. It can look like people on the streets with no sure home. It can look like the inability for homeless shelters to provide to a whole community of impoverished which exceeds their space or materials. Poverty can look like many things and, as the dictionary definition points out, it does not necessarily mean the complete absence of belongings or wealth, but less than what is “socially acceptable.” Despite this being the immediate image of poverty in the US or possibly other Western nations, a Google Image search of the word “poverty” first brings up image results of impoverished peoples in distinctly non-Western locations and communities. Many of the people appear to be non-White, and the first recommended sub-category for the image search is “Philippines.” So this begs the question, what does poverty look like in other cultures, or rather, what do we think it looks like?

Google Image results for “poverty”

Undoubtedly, poverty exists in other countries and is an issue of utmost importance, seriousness, and severity. However, in some cases, Westerners apply the term to lifestyles which are not actually low-quality or impoverished.

Subsistence Living and the Value of Indigenous Ecology

Subsistence living is one of the multiple key concepts in Vandana Shiva’s eco-feminist text, Staying Alive. Shiva distinguishes between two types of poverty, one being actual, real poverty worded as “misery as deprivation,” and the other being “culturally perceived poverty” (8). The latter refers to subsistence living, or a way of living which is self-provisional, where a groups’ belongings and sustenance is grown, made, and gathered by themselves. Shiva points out that this “need not be real material poverty: subsistence economics which satisfy basic needs through self-provisioning are not poor in the sense of being deprived,” yet many Westerners are compelled to describe it as such because these groups live without the modern luxuries so many of us view as necessities. These lifestyles, often willingly practiced by indigenous groups, do not equate with what some see as a “good” life and so Westerners subsequently believe that these methods of self-provision ought to be changed, and these people ought to practice the same commodification and industrialization that we do.

But willing subsistence living is not synonymous with poverty, and in fact it can provide benefits for those who are accustomed to its practices, as well as for the environment around them. For people, naturally grown and harvested foods are more nutritious and nourishing than processed ones. Housing built from natural, local materials by local communities can be better suited and adaptable to the climate of the places they are built in. Indigenous methods of farming can prove to be more resourceful, in touch with the needs of the ecosystem, and efficient from a long-term approach. As described, subsistence living has more pros than Western society may realize. Catherine E. Burnette, Caro B. Clark, and Christopher B. Rodning describe the advantages of subsistence living in the journal “Living off the Land”: How Subsistence Promotes Well-Being and Resilience among Indigenous Peoples of the Southeastern United States. The journal states, “Subsistence activities may inherently promote well-being by simultaneously and organically promoting physical activity, healthy nutrition, and subjective well-being, along with family and community cohesion” (Burnette et al. 376).

Additionally, subsistence living can foster “a sense of shared responsibility and indebtedness” that community members feel towards the environment, especially when combined with indigenous ideologies regarding nature (Burnette et al. 391). Subsistence living does not focus on how to quickly and repeatedly profit off of the land, but rather how to give back to it as much as it gives to its people, much unlike Western approaches to land use. By choice, this method of living and provision is not industrial nor is it highly profitable. For this reason, Western society feels compelled to “improve” it, and steps in to help.

The Loss of Choice and its Impacts

Although stepping in to alter subsistence living due to its perceived association with poverty may be seen as a heroic effort, it has extensive consequences on both land and people. By enforcing a Western standard of living because it is deemed more sophisticated and satisfactory, it perpetuates the power and influence of colonialism. It not only spreads Western beliefs, but also Western economic growth by pushing those who practice subsistence living to financially support commodification. In the previous section, it is mentioned that subsistence living can provide health benefits to human communities and individuals. But after being removed from subsistence living, several studies suggest that indigenous groups are subject to higher rates of health issues as a result, “Prior research posits that the high rates of diet-related diseases among indigenous people may be related to historical oppression in the form of losses in knowledge about traditional foods (Ruelle and Kassam 2013). In fact, before the 1950s, diabetes was said to be unheard of among indigenous peoples, and they were thought to be immune (Satterfield et al. 2007)” (Burnette et al. 373). Historical oppression of indigenous groups’ whole lifestyles poses a threat to the physical body as well as psychological well-being.

But it is not just the human which is impacted by this loss of subsistence. Part of the Western approach to ending perceived poverty while also strengthening Western economic and industrial growth is to get indigenous groups to assimilate into Western society. And part of that process is to “incorporate or absorb the land and resources of Indian [indigenous groups,” according to Melissa L. Meyer’s journal, "We Can Not Get a Living as We Used To": Dispossession and the White Earth Anishinaabeg, 1889-1920 (370). In doing so, land which was once used sparingly and respectfully via subsistence living falls victim to exploitation. We need not look to other countries to see colonialism forced upon indigenous groups when so many indigenous groups deal with colonialism right here in the US. The same text states that, in the case of assimilating the indigenous group Anishinaabeg, US social engineers envisioned the Anishinaabeg producing “specialized cash crop” which could be marketed and sold, highlighting the Western priority of commodification (Meyer 378). And in 1900, farmers faced a serious lack of “crucial subsistence resources” because American policy makers who held power over the agricultural assimilation of the Anishinaabeg did not account for how seasonal shifts in the environment played into Anishinaabeg approaches to well-being. As a result, the American policy makers failed to protect or aid these environmentally-mindful approaches. This failure of Westerners to grasp even the most basic indigenous approaches to agriculture quickly drained natural resources.

Also at the cost of nature and the Anishinaabeg, another similar issue occurred when US lumber companies rapidly exploited red and white pine wood near an Anishinaabeg reservation. In order to maximize and rapidize the production process, lumbermen created a channel of dams in order to transport the logs by water, a channel which cut through a lake used for harvesting wild rice. This prioritization of commodification over protection of the land--a factor of indigenous subsistence living--was not without consequence. Meyer describes the situation, “Damming the eastern waterways flooded swamps and marshes that supplied crucial subsistence resources. At times, dams completely washed out the wild rice crop. Floodwaters also engulfed low-lying Indian [indigenous] gardens on river bottom land. Clear-cutting timber caused erosion and muddied streams, choking aquatic life. Piles of brush and ‘stumpage’ created prime conditions for fires…” (382). All of this was the result of just one instance of disregard for subsistence living which highly jeopardized the Anishinaabeg’s subsistence economy and the health of the environment. Over time, as Western economy and industrialization overpowered subsistence-based peoples, it became impossible for them to live harmoniously off of the land, effectively marginalizing indigenous culture and nature. This is the cost of meddling with subsistence living in the name of saving people from what we might believe to be poverty. It threatens humans’ health, indigenous values and practices, and nature.

Conclusion

In an effort to enforce what Westerners deem a “socially acceptable amount of money or material possessions,” we face an all too real risk of creating real poverty not just for us but for the Earth. As stated by Vandana Shiva, “The erosion of the resource base for survival is increasingly being caused by the demand for resources by the market economy, dominated by global forces” (11). This perpetuates a vicious scenario wherein resource-intensive land use puts subsistence living communities at an economic disadvantage, and in viewing their lives as poor not because of this but because they are self-providing, they are forced to assimilate into Western ideologies to survive. All this while their beliefs and ways of living are continuously oppressed at the cost of ecological health. We need to re-define poverty in order to be able to distinguish between actual deprivation and simply a difference in cultural practices. It is of high importance that people understand the value of subsistence living, especially to indigenous groups, in order to recognize when the efforts of ending poverty are doing little beyond feeding capitalistic and colonial growth.

Works Cited

Burnette, Catherine E., et al. “‘Living off the Land’: How Subsistence Promotes Well-Being

and

Resilience among Indigenous Peoples of the Southeastern United States.” Social

Service Review, vol. 92, no. 3, 2018, pp. 369–400., doi:10.1086/699287.

Meyer, Melissa L. "We Can Not Get a Living as We Used To": Dispossession and the White

Earth Anishinaabeg, 1889-1920: Melissa L. Meyer: Academic Room. 1991,

www.jstor.org/stable/2163214.

Poverty.” Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/poverty.

Shiva, Vandana. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development. North Atlantic Books,

2016.

Comments